Whoever has travelled in Turkey could tell amazing stories about the proverbial hospitality of this land. The unavoidable “Hos Geldiniz!”, the welcome that even passport control policemen greet foreigners with, is a surprising declaration of availability and opening. Crossing Turkey on a motorbike, in Summer, allow to collect countless greetings by motorists, farmers or walkers. But when, between Antalya and Kayseri, a century old fig tree loaded with fruits show itself in a provocative manner to the hungry motor bikers, to give in to the temptation becomes unavoidable.

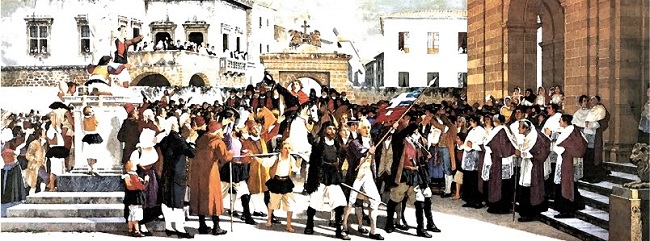

I confess, with shame: we parked the bikes, and as very bad Italians we began to pillage all that wealth … and in the middle of it, a nearby house door opened, and a farmer came running towards us. Frightening childhood stories about fruit thieves, salt loaded shotguns and shameful flights flashed in our minds… and when the farmer reached us, he tended us not one, but two plastic bags, apologizing for their small size, and helped us to choose the better figs, thanking us for appreciating his fruits, inquiring about our ideas about his country and asking if in Italy we had figs as good as his ones. It probably happened thousands times, in that same place: perhaps to Alexander’s soldiers, repelled from Termessos and marching against Sagalassos, perhaps to the merchants along the last legs of the Silk Way, coming from the Asians steppes, or to refugees coming from many devastated countries to look for hospitality in this Land. A land shaken by earthquakes, with extreme climactic excursions, though unbelievably fertile, where who has been strong enough to live has always had the chance to prosperate. Even a mere list of the civilizations developed in Anatolia would be too long: Hatti, Hittites,Persians, Greeks, Romans, Byzantines, Seljuks, Ottomans have succeeded one another mixing up into a crucible of heritages collected and absorbed by the successor ones, until the catastrophic collapse of the Ottoman Empire, in the XXth century. It was to preserve this heritage that the founder the new Turkish Republic, Mustafa KemalAtatürk, patronized the foundation of the Museum of Anatolian Civilizations, in Ankara, where he is quoted: “A People cannot say to master a Fatherland if it does not master the knowledge of all Civilizations that have been lived there”. It’s an exhortation to preserve the historical and archaeological heritage that has been followed, and prized: most of the about 30 million tourists that have been able to appreciate Turkish hospitality, have visited its archaeological sites and museums. But not only tourists are guests at the archaeological sites.

Every year, thousands of young archaeologists from all over the world are engaged in digging campaigns in Turkey, and among their discoveries, one is to be welcomed as friends. “The excavation workers often invited us to their houses for breakfast” tells Ben Irvine, a young British archaeologist, researcher at the British Institute At Ankara (BIAA), that has worked at the site of the ancient Hittite capital Hatusha, at Bogazköy. “Even weddings or other family celebrations were opportunities to have us as guests, no matter if they were for close families or not.” Ben is favourably impressed by the Turks’ pride for their historical heritage “It’s a state of mind that helps to create a positive attitude for the sites conservation, although sometimes it can give problems, such as the diplomatic issue of excavation permits denied to German archaeologists in the recent case of the sphinx from Hatusha…”Indeed, hospitality duties are never on one side only: an Hittite sphinx, sent to Germany in1915 for restoration, has been returned only in 2011, after the diplomatic row recalled by Ben. But usually, relations with foreign archaeologists are warm. “Although I was at my first assignment as a responsible of an excavation area, I have been given confidence and total independence from the first moment” Enrico de Benedictis, 29, Italian archaeologist having worked at Alalakh, near Antakia, states. “I was responsible for good or bad, and though there was no indulgence towards mistakes, the more experienced ones were always available for advise and explanation, in a true passage of knowledge. I never met such an availability in other countries where I worked, let alone in Italy!”Vera Costantini, researcher in Turkish Language and Literature at the “Ca’ Foscari” University in Venice, lived three years in Istanbul, doing her researches at the Basbakanlik Osmanli Arsivi. “Turkish Archives work along the highest European standards” she declares. “The reception from the archive staff and Turkish colleagues to me and my research interests has always been truly attentive, stimulating beyond any expectation.

”Chiara Vitali, 36, underwater archaeologist who worked on the submerged harbour at Liman Tepe, at Urla, near Izmir, has enjoyed the Turkish attitude towards guests as well, and she remarks an unusual point, interesting for who does not know about the woman condition in Turkey “In the University of Ankara’s campus at Urla, where we stayed, Sunday was cleaning day. Everybody had some duty, but I was not allowed to do anything, as ‘a guest’. Only a few times I succeeded in give some help.”

Chiara recalls the curiosity of her Turkish colleagues towards foreigners “The questions they ask are always aimed to understand our way of life and our mind, with no judgment or criticism: sometimes they agree, some other they don’t, but I never heard any reproach or cultural or religious closing.”

She is also impressed by the dedication to the conservation of the historical heritage “I wish we had in Italy the same spirit for everything representing the past history… It is not only care, it is real respect!” The same respect is paid to the legacy of any foreigner that has shared the land upon which they live, or where they are buried. Even invaders have right to it: the place where the Australian and New Zealand Armed Corps (ANZAC) landed in 1915, near Gallipoli, has been renamed “Anzak Koyu”. Atatürk, who was the military commander who repelled the invasion, beginning his rise, commemorated the fallen with these words: ” Those heroes that shed their blood and lost their lives… you are now lying in the soil of a friendly country. Therefore rest in peace.

There is no difference between the Johnnies and the Mehmets to us where they lie side by side here in this country of ours… You, the mothers, who sent their sons from far away countries wipe away your tears; your sons are now lying in our bosom and are in peace. After having lost their lives on this land they have become our sons as well.”And every April 25th, thousands of Australians and New Zealanders come in peace to celebrate “Anzac Day”, the commemoration of their fallen, in a land now friendly, and always hospitable.

(© 2012 Piero Castellano for mediterraneaonline.eu)