It has happened in the past, it will happen in the future. It shouldn’t happen at all. This is the story of poverty.

In the past, poverty was often associated with homeless people on the streets or jobless people in the breadlines. More often than not poverty wore faces of elderly men, drinking themselves to death.

In Slovenia, now an independent Central European state but formerly a republic of the former socialist federation of Yugoslavia, for many decades poverty was not very visible. Socialism did not know jobless or homeless people. For a socialist country it was not appropriate to admit that some of its citizen struggle with poverty. Poverty was associated with the corrupted capitalist West.

At the time, journalists could not publish data about poverty as they did not exist. Occasionally, some journalists nevertheless wrote about people facing hardships in socialism. The system could be attacked through the portrayal of personal stories. They did so because they believed although the system was successful and good, it nevertheless needed aid in becoming even friendlier, more human. Criticism was a way of helping out. They said that journalists helped ensure that bureaucracy avoid injustice.

After declaring independence in 1991, Slovenia stepped on the road to capitalism. In the country where people were used to being equal, some jumped ahead and managed to prosper, but more and more were left behind. Today, even people with minimal wages, own homes and cars are facing poverty.

Take the stories of Suzana and Pavle for an example. Both of their families were hit hard by unforeseen events.

Suzana’s husband had a fatal heart attack at 41, three hours before they were off to holidays. He left behind a wife and two children, one salary and two bank loans. Pavle’s wife died fifteen years ago; seventeen days after the birth of his second son. Ever since then he is taking care of them. Once he asked the social services for help with some paperwork which will help him financially. They ignored his plea and started bothering him for failing to follow some bureaucratic procedures related with providing a custodian for his sons after his wives death. “Nobody told me they need a custodian after she died. I never asked the social services for help before; I did not do it after either, because they were rude to me.”

Statistically, Suzana and Pavle are not poor. They earn more than minimal wages. Nevertheless, they struggle daily.

Are Slovenes poor? That depends on definition of poverty. Subjective poverty is based on the personal perception. Objective poverty is measured by standard indicators, such as wages and education. The relative poverty is defined as inequality in income, and the absolute poverty as the number of people who don’t earn enough money to survive. In Slovenia, 12 percent of population earn less than 545 euro net per month and fall into the last category.

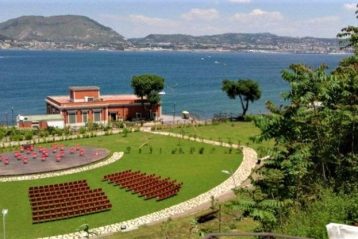

One of the people who daily face the consequences of poverty is Anita Ogulin who runs the local branch of a national NGO Zveza prijateljev mladine Slovenije (Slovenian Association of Friends of Youth). A few years ago Anita Ogulin realized that many of the children she met through different activities of her NGO have never been on holidays. So she started a national campaign called Pomežik soncu (A Wink to the Sun). Since then many of her little friends have seen the sea for the first time.

This year only 340 children will be able to go on vacation through her program, much less than in the past. The recession hit Slovene economy pretty hard; donors, who enabled the program, were able to donate a lot less money than in the past.