In the ancient Mediterranean world the concept of female sexuality attracted a very different kind of attention than that received in modern times. Nowadays, countries of Judaeo-Christian traditions as well as Muslim countries view sexuality (especially female sexuality) as tabu’, depriving it of any connection with the experience of pleasure and reducing it to a simple act of procreation in which the woman plays a passive role.

Such a vision has contributed, particularly in Christian-Catholic countries, to the perception of sexuality outside wedlock as impure if part of an heterosexual relationship and even as an abnormal act when in the context of homosexuality, except in the case of the recent acceptance of gay weddings even in the super Catholic Spain.

Going back in time we find that, despite the scarcity of significant iconographic documentation, the sphere of Eros in ancient Egypt has handed down several texts. Among these there is the so called “Turin erotic papyrus” dating to XX Dynasty

( 1186-1069 BC), of Deir El-Medina and currently preserved in the Egyptian Museum of the Piedmont capital. This document, divided in two parts, one satirical and the other erotica, describes in its second part the amorous encounter between a bearded peasant

and a courtesan, combining the wealth of details with a notable sense of humour.

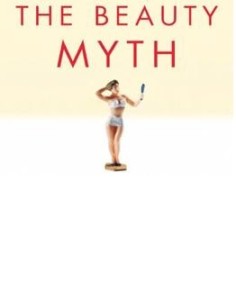

It narrates the preparations undertaken by the woman to beautify for the encounter, covering herself in creams and cosmetics and donning a wig decorated with flowers.

This image of the woman as free interpreter of sexual customs gives the measure of the emancipation achieved by the Egyptian woman, the most liberated of her contemporaries of the ancient world.

In the protohistoric period, in Mesopotamian civilization (circa 3000 BC), sexuality enjoyed a place of honour on a par with the sphere of the Divine, the cycles of nature and the fertility rites, as it was characteristic of societies whose survival depended on agricultural practices invariably strongly linked to pagan worship. A practised ritual was “hierogamy” (from the Greek hieros gamos), the sacred marriage in which the priest representing the deity engaged in sexual intercourse with the priestess symbol of female divinity to guarantee the fertility of the land. It is widespread opinion that from this ancient tradition originates the phenomenon of the so called sacred prostitution and the role of the “hierodule”.

Herodotus narrates how, in Babylon, was custom for every woman to become a prostitute in the Goddess Ishtar temple at least once in her lifetime. The same custom is again found in the Phoenician-Punic civilization who erected temples dedicated to the Goddess Astarte and which were often built on high promontories facing the sea as in the case of the Sella del Diavolo on the gulf of Cagliari, currently object of archaeological excavations. Astarte was the protectress of sailors, the latter undoubtedly willing to pay her homage by turning their attention to the priestesses and thus contributing to fatten up the coffers of the temple. Hence the female, in her role of hierodule (meaning ‘temple slave’ in Greek) held a pivotal position which is not recognisable in our civilization today or in the Judaeo-Christian and Muslim worlds in general.

Beyond normal reproductive function – or pure carnal pleasure for the hedonist – in classical civilizations sexuality was a means of precise educational purposes, including relations with members of the same sex. These were prevalent practices, with the exception of Etruscan society where the two sexes lived a neatly separated existence.

We shouldn’t forget the religious community founded by the poetess Sappho on the island of Lesbos in honour of Goddess Aphrodite. The community of this famous poetess was much renowned in the education of girls from good families and it mirrored in its status the male associations in which boys were taught poetry, music but also athletics and the military arts.

Residency inside these communities was a kind of initiation to adult life:

the education of girls was geared to marriage, they were taught singing and dancing, the search for beauty, refinement and love. Homo-eroticism was practised between the girls and with Sappho and today we retain fine examples of her poetry inspired by her love for a girl named Attis. There was serene acceptance of this kind of interaction, indeed encouraged since it was considered as blessed by Divinity and as a precursor to heterosexual love in matrimony. Homo-eroticism practised in similar male congregations was equally approved.

“We have hetaerae for pleasure, concubines for daily satisfaction of the body, wives to bear us legitimate children and to faithfully care for our homes”: This was the

pseudo-Demosthenian prayer “Contro Neera” that defined the different conditions of female Eros in the Athens of the classical age. The top of the social scale was occupied by the woman taken in matrimony.

The purpose of marriage was the procreation of legitimate children who would inherit and preserve the family wealth. The husband held his wife in high regard as the mother of his children and the organizer of the oìkos (family home) but rarely his was a genuine sentiment of love for a woman who,generally, he had not chosen personally and often he had not met prior to their nuptials. The concubines, “pòrnai” in Greek, were the prostitutes who, under the Athenian Solon, exercised a true state monopoly of services on dedicated public soil. Finally, the hetaerae were elegant and cultured courtesans, often with influential powers, much liked by politicians and thinkers alike. These characters were in contrast with the general condition of women to whom access to culture and public life was denied.

The eroticism of women in Roman society did not differ to a great extent. The wife was in charge of the home and responsible for bearing legitimate children after marriage which generally took place before she reached puberty, unlike in the Hellenic customs.

It should not surprise that this forced cohabitation between people mutually unwanted and with huge generation gaps frequently gave raise to extra-marital affairs on both sides albeit more tolerance was shown to the male transgressor. Therefore, at least for the ordinary woman of good family, sexuality was rather repressed, certainly under-valued and subjugated to that of the man.

Naturally, male and female prostitution was widely practised in ancient Rome, perhaps in a less “institutionalised” form compared to Greek society. It is true that we have greater testimony of male homosexuality, suffice to think of Emperor Adrian who suffered deeply after the death of his young lover Antinoo to whom he dedicated sensitive love verses. Nevertheless, female homosexuality should not be considered absent notwithstanding the absence of iconographic and written sources. The findings of several brothels in Roman centres give testimony of an ordinary and well known custom, whose “practitioners” were obliged to register on official lists and undergo regular health checks, wear yellow clothes and pay a State tax despite the limited recognition of their citizen rights.

Of course, we are looking at a concept of morality infinitely remote from today.

Between erotic papyrus and pòrnai, we should not be fooled by a female Eros that was perhaps less inhibited than ours. It is important to remember that, despite few exceptions, emancipation of women also from the sexuality perspective is a rare commodity today like it was in the ancient world.